How Corruption in the City of Orlando Made its Way to the 2024 Opening Conference of the Supreme Court of the United States

Orlando’s Corruption Crisis

It’s one thing for local government corruption to cause a stir within the community. It’s another thing for one lone city’s entire government apperatus to be the focal point of a conference between the Justices of the United States Supreme Court, due to corruption. Typically, once detected, corruption is taken care of before SCOTUS even knows anything about the operations of a municipality. In the 1980s, a masive corruption scandal in Chicago known as Operation Greylord resulted in more than 92 public officials being indicted. A total of 93 people were indicted, including 17 judges, 48 lawyers, 10 deputy sheriffs, eight policemen, eight court officials, and state representative James DeLeo.

What SCOTUS has before it now, and which they will discuss at their Opening Conference on September 30, 2024, is reminiscent of what happened in Operation Greylord.

So, how did this happen? Where was law enforcement? What impact does this have on the legal issues facing former president Donald J. Trump? And why Orlando?

Lowndes Law Firm

It began with a local law firm, Lowndes, Drosdick, Doster, Kantor & Reed. The firm is prestigious and touts its extensive connections via its “Broad Reach”. The firm even has representation on the local judicial nominating commission, which wields the incredible power of composing a list of lawyers to be submitted to the Governor for appointment to the bench in the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court. The firm’s appointee, Tara Tedrow, selected judges John Beamer, Vincent Chiu, Eric DuBois, Lydia LaBar, Gisela Laurent and Barbara Leach as nominees to be appointed by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. John Beamer, who was recently reprimanded by Florida’s Supreme Court, is key to the SCOTUS conference.

How does one get onto this coveted list of potential judges who do not have to have an election and be chosen by the People? No one really knows. The JNC has the exclusive authority to shape the bench however they want. If a law firm has the power to create the bench, what could possibly go wrong if someone from the firm ended up in court, or needed a favor?

Julia Frey of Lowndes, Drosdick, Doster, Kantor & Reed

Enter attorney Julia L. Frey, daughter of the late congressman Lou Frey, who was also an attorney at Lowndes prior to his death.

Frey found herself in a property dispute with Moliere Dimanche over title to a residence she claimed she owned due to the death of a former elderly “client”, Qurentia P. Throm. At the outset of the dispute, Frey and her sister, Lauren Frey-Hamner made a set of claims to Orlando police in late 2022 that didn’t pass the smell test. Whatever interest they claimed in the property dispute was deemed “fishy” by Orlando police sergeant Michael Massicotte, especially with an attorney and her sister sneaking around property belonging to one of her clients. After a brief investigation, Sgt. Massicotte advised Frey to go home and seek a civil remedy concerning her interest in the property.

Instead of going through the courts as sergeant Massicotte had instructed her to do, Frey did the unthinkable: she and Lauren partnered with rogue Orlando police officers and committed an armed home invasion weeks after the property dispute arose. The officers had no warrant, nor the authority to enter the home under Florida law. After the home invasion, the OPD officers, Aaron Goss, Adam Cortes, and Brent Fellows, changed the locks on the house and handed the keys over to Lauren Frey-Hamner. Hamner was now the new owner.

The most glaring of the many problems in this scenario is Fla. Stat. § 732.806, which declares gifts made to lawyers, their relatives, or their law firms from the estate planning documents of a client void as a matter of law. Statutes like this one became law in nearly every state in America as the result of a controversy in 1992 surrounding attorney James D. Gunderson, who was embezzling millions from the estates of his clients. To ensure that the public did not lose trust in officers of the court, many laws went into effect declaring such benefits void in the eyes of the law.

Both Julia Frey and her sister, Lauren Frey-Hamner, were disqualified people in relation to the property dispute. But this didn’t stop Julia and Lauren from trying anyway, and initiating the home invasion.

Orlando Police and Fake Warrants

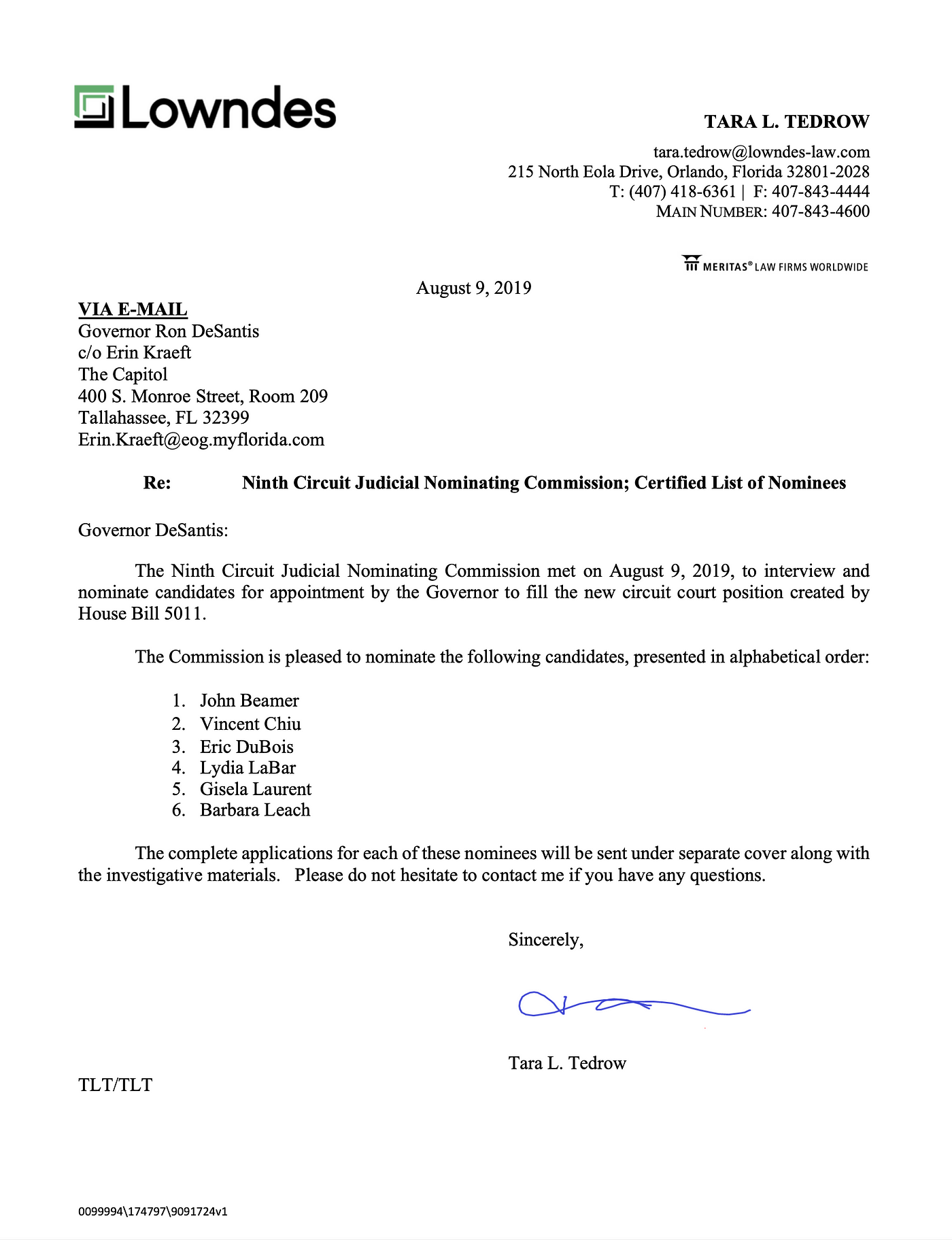

Dimanche was not present when the home invasion occurred, but after he found out what had happened, Dimanche dialed 911 and reported the break-in. To cover up what the officers had done, the 911 operator sent OPD officer Nicolas Luciano Montes and two other officers to arrest Dimanche under the guise of a fake arrest warrant. Montes created a fraudulent court case, made up the bond amounts, and processed a false affidavit with this information on it with the Orange County jail.

In the affidavit given to the Orange County jail by Montes, he falsely attested to being an “Orange County Deputy”, supplied the bogus “court case number 2022–00394672” and the bogus agency number “2022–00407544”. The date of the arrest is also critical to how this issue ended up in the Supreme Court of the United States.

First, Section 30.15(1), Florida Statutes, provides that sheriffs, in person or by deputy, shall execute in their respective counties all process of the courts of this state which is executed in their counties. No provision of general law authorizes or requires a municipal police officer to execute or serve arrest warrants or any other criminal process which is issued by the courts. This comes as a surprise to most people because there is a misconception that sheriff’s deputies and police officers are one and the same.

They are not.

Under the law, municipal police are confined to traffic infractions, misdemeanors, or other crimes that happen in their presence, which they must then contact the sheriff to handle. Therefore, if a city cop pretends to be a sheriff’s deputy and makes an arrest, it is a kidnapping.

Second, the “court case number” supplied by Montes leads to nowhere. A quick search of that court case number with the Orange County Clerk of Courts yields no results. In reality, he took the OPD investigation number “2022–00394672” and used it in the space for the court case number. He then made up a completely bogus agency number, which appears to be the beginning of a phone number using Orlando’s “407” area code, so that the “agency number” and “court case number” would not be identical. This tactic worked on staff at the Orange County jail and Dimanche was booked.

But this also needed to be covered up.

A Second Bogus Warrant

Enter judge John D.W. Beamer.

Frey’s initial plan was to simply have Dimanche put in jail so that she could take possession of the residence without resistance, but the scheme spiraled out of control. Dimanche had been kidnapped by Montes and there was no actual court case to refer to for the purpose of justifying the false arrest. Frey asked Beamer to issue a warrant for Dimanche’s arrest based on the charges created by Montes, and Beamer complied. On November 21st, 2022, a day after Montes had taken Dimanche to jail, Beamer issued the warrant. By that time, Dimanche had already bonded out of jail and the bonds were insured on the non-existent court case.

After Beamer issued the warrant, the clerk of court, Tiffany Moore-Russell, went back and wrote in the new court case number on the bond tickets andthe affidavit filed by Montes.

Weaponization of the State Attorney’s Office

Upon his release from jail, Dimanche sued Frey, her sister and the Orlando police officers for the break-in and kidnapping in federal court. The case was assigned to district judge Carlos E. Mendoza. In response to this civil rights complaint, Julia Frey asked prosecutor Richard I. Wallsh to increase the charges against Dimanche in order to deter him from pursuing the lawsuit. Wallsh complied and Dimanche was faced with a 1st degree felony and the possibility of 30 years in prison.

In order for Wallsh to succeed at the prosecution, he needed the help of a judge who would help keep the undisclosed relationship with Frey under wraps.

Enter judge Mark Blechman.

Blechman, who maintained his own personal relationship with Julia Frey along with his wife, presided over the case for 186 days until the Florida Bar and the Judicial Qualifications Commission received complaints about a 3-way conflict of interest that detailed a 40-year relationship between Frey, Wallsh and Blechman. At the same time, Dimanche, who represented himself pro se, performed a legal strategy known as the Notice of Removal and transferred the criminal prosecution to federal court. Dimanche’s basis for removing the case to federal court was due to Frey’s influence over the Ninth Judicial Circuit, which rendered a fair trial impossible. The removed prosecution was also assigned to Carlos E. Mendoza.

Once removed to federal court, an evidentiary hearing took place wherein Wallsh was required to testify about his relationship with Julia Frey and any potential bribes he may have taken. Since Wallsh was not a member of the Middle District Bar, he could not manage the now-federal prosecution. Prosecutor Brian Stokes was assigned to the now federal prosecution by the 9th Judicial Circuit state attorney, Monique Worrell.

This hearing changed the trajectory of everything. It centered around Wallsh’s history of using the office of the state attorney to protect his friends. In 2013, Governor Rick Scott signed Executive Order 13–60 after then-serving state attorney Jeff Ashton told the governor that Wallsh had consulted a defendant in a criminal case named Roni Elias in both the criminal charges facing Elias, and the civil litigation commenced against Elias in a property dispute. Only problem? Wallsh was never a criminal defense attorney, nor did Elias hire Wallsh to represent him in the civil action.

Dimanche later learned that Roni Elias was Wallsh’s and Ashton’s landlord after Wallsh submitted an affidavit concerning allegations of selective prosecution. This information was not provided to the governor. The charges against Elias were transferred to another jurisdiction and ultimately dropped.

In light of the Roni Elias issue, compounded with the fact that Wallsh was fixing another case for Julia Frey, Mendoza called Wallsh to testify. For some reason, Wallsh never took the stand. After the hearing, Mendoza accepted additional evidence but ultimately remanded the case to the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court without ever putting Wallsh on the stand. Dimanche appealed Mendoza’s remand order to the Eleventh Circuit while he returned to the Ninth Judicial Circuit to contend the allegations in state court. The basis for that appeal was that Wallsh’s testimony was required to make a reliable determination as to the likelihood of a fair trial in the Ninth Judicial Circuit.

House of Cards Falling and a Fake Prosecutor

As soon as the case returned to the state court, judge Mark Blechman immediately entered an order recusing himself from the case to avoid “the appearance of impropriety”. Monique Worrell also booted Wallsh from the case altogether. The case was reassigned to judge Tarlika Nunez-Navarro, and for a while, no prosecutor was designated to replace Wallsh.

Enter Andrew Edwards.

Edwards was not a real prosecutor. You wouldn’t know if you didn’t ask, and the Golden Rule amongst lawyers is: Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

For a while Dimanche didn’t ask until after Edward’s attended a deposition Dimanche had scheduled with one of the officers who assisted Frey with the break-in. The officer, Rabih Tabbara, resisted the deposition until ultimately being placed under oath and killing the entire prosecution instantly.

During the deposition, Tabbara provided testimony that he had lied under oath to manufacture probable cause, he called in a false crime on Dimanche, he planned out criminal activity with Julia Frey, and he omitted the fact that he had handcuffed and falsely imprisoned Dimanche from his police report. Tabbara was later taken off the beat and stationed at an information desk in OPD’s headquarters on South Street.

At the end of the devastating deposition, Edwards pulled Dimanche to the side and asked for a quick resolution to the ordeal. Edwards stated that he would no longer list Tabbara as a witness, and that jurors did not need to see a “sneaky probate lawyer like Julie Frey” taking the stand. Edwards offered to drop the felony counts filed by Wallsh if Dimanche pleaded No Contest to a misdemeanor. Edwards needed a plea of any sort in order for Frey to prevail in the Civil Rights lawsuit pending in federal court. Dimanche declined and continued dismantling the State of Florida’s case.

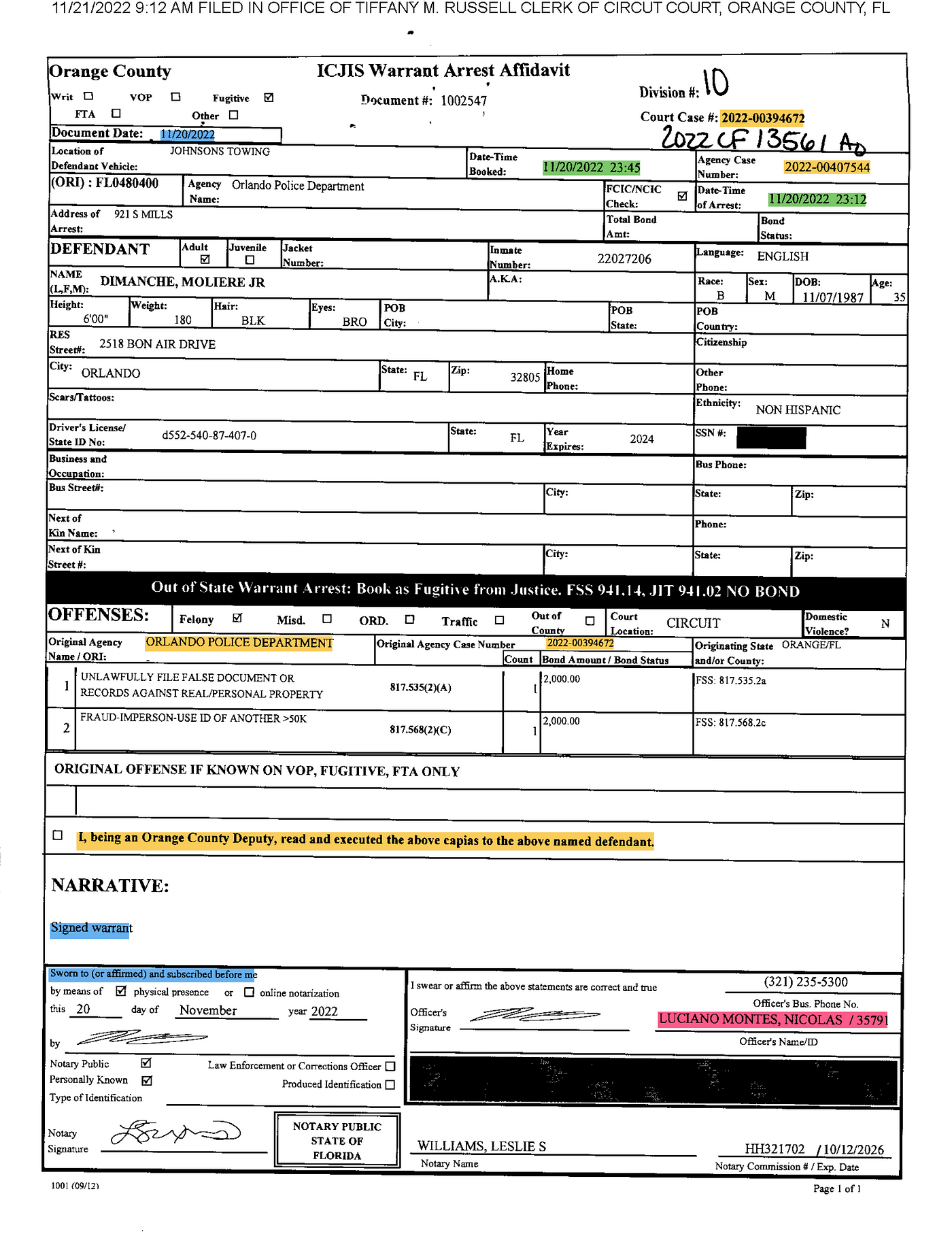

Edwards was in no mood to prosecute a losing case, but he also refused to lose. He and Nunez-Navarro had a plan: make Dimanche miss court so that they can lock him up in jail without a bond. Tarlika Nunez-Navarro scheduled an arraignment after Blechman’s recusal order.

The hearing was set for June 7th, 2023. But on that date, Nunez-Navarro put a sign on the outside of her courtroom door, asserting that the hearings set for the 7th would take place on July 9th instead.

This was a lie.

Nunez-Navarro secretly rescheduled the arraignment for June 8th, 2023. If Dimanche had shown up on the 9th, he would have been hauled off to jail for failure to appear. Dimanche found the notice suspicious. Additionally, the court docket did not list a hearing for June 9th, 2023. Dimanche had one choice: show up every day, out of an abundance of caution.

Dimanche showed up on June 8th, 2023 and his name was called for arraignment. Edwards was not present, and Nunez-Navarro seemed surprised to see Dimanche. After the bizarre hearing, Dimanche left and began investigating Edwards. These individuals were simply not behaving as one would expect attorneys and judges to behave.

Dimanche discovered Florida Statute 27.171(1). It relates to appointed assistant state attorneys and their designations by the elected state attorney. It’s what gives them the power to prosecute. It reads:

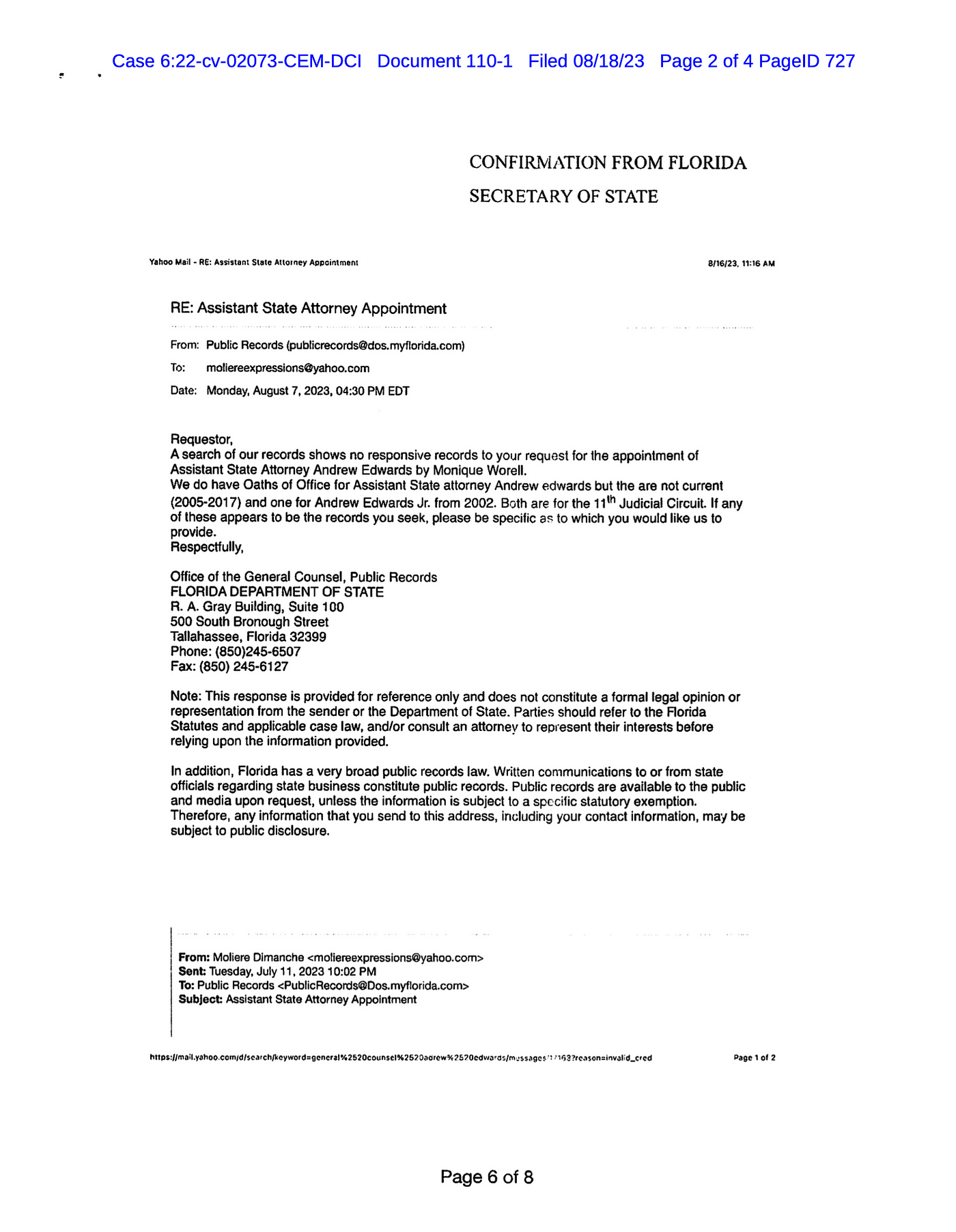

Given Edwards’ unprofessional method of prosecution, Dimanche suspected that he was not really a prosecutor, and probably not even a lawyer at all. After checking the county records and finding Oaths and Appointments for Wallsh and Stokes, Dimanche could not find one for Edwards. This prompted Dimanche to contact the office of Cord Byrd, Florida’s Secretary of State, and inquire further.

Dimanche received both a phone call and email correspondence confirming that Andrew Edwards was not an authorized prosecutor in the Ninth Judicial Circuit. They stated that Edwards used to be a prosecutor for Katherine Fernandez-Rundle in Miami from 2005-2017, but that no elected state attorney in Orange County had ever given him the job.

So what on Earth was Edwards doing in the state attorney’s office signing charging documents?

Upon making this discovery, Dimanche filed a Petition for a Writ of Mandamus with the Florida Supreme Court demanding that the prosecution in the name of Monique Worrell by a fake prosecutor be dismissed with a commanding writ. The Florida Supreme Court transferred the case to Florida’s Sixth District Court of Appeals to resolve.

During this time, Monique Worrell had designated special counsel Elliot Kula to handle the case in the Eleventh Circuit appeal due to the conflict of interest with Richard Wallsh and Julia Frey.

At the same time, the Judicial Qualifications Commission received a complaint about Tarlika Nunez-Navarro regarding the sign she put on her door, her attempt to make Dimanche miss court, and an instagram post she deleted about doing Mark Blechman’s bidding in his absence. A week after the complaint was filed, Nunez-Navarro signed an order recusing herself from the case before she resigned from the judiciary altogether and took a position at the Benjamin Crump School of Law as the dean. At the time of her resignation, she had a pending application to become a justice of the Florida Supreme Court.

Things were getting so far out of hand and Dimanche’s determination to defeat the bogus allegations was becoming a bigger problem than they had bargained for. Who was going to save the day?

Courthouse Extortion

Enter judge Luis F. Calderon.

After Nunez-Navarro’s recusal and resignation, Calderon assigned the case to himself. At this time, he had the specific judicial assignment as the post-conviction judge. This meant he lacked jurisdiction over cicuit criminal cases, but he didn’t care. He wanted the Dimanche case. The first thing he did was cancel all of the court dates that had been previously scheduled before Tarlika Nunez-Navarro. Then he didn’t do anything else. No new court dates, no hearings, nothing.

Dimanche checked the docket every single day, and no new court dates were listed. Perhaps it was due to the mandamus in the 6th DCA? Or maybe the appeal of Mendoza’s order in the 11th Circuit? It seemed very unusual that a judge who was newly assigned to a case did not, at a bare minimum, issue orders setting new court dates. The only dates on the docket were the previous court dates set by Tarlika Nunez-Navarro, and they all had the word “CANCELLED” beside them.

It wasn’t until the first “CANCELLED” court date arrived that Dimanche found out why Calderon hadn’t taken any action: he was waiting for Dimanche to miss the first “CANCELLED” court date. The moment it happened, Calderon issued a warrant for Dimanche’s arrest for failure to appear.

https://cdn.embedly.com/widgets/media.html?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fembed%2FoSHmgEIpPjE%3Ffeature%3Doembed&display_name=YouTube&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DoSHmgEIpPjE&image=https%3A%2F%2Fi.ytimg.com%2Fvi%2FoSHmgEIpPjE%2Fhqdefault.jpg&key=a19fcc184b9711e1b4764040d3dc5c07&type=text%2Fhtml&schema=youtubeCalderon issues dirty capias for Dimanche after using “a sign was on the door” trick.

Dimanche did not know about the warrant until he received a voicemail from Edwards stating that there were “no scheduled court dates in the foreseeable future”. The voicemail was unusual because Edwards had stopped communicating with Dimanche once the petition for writ of mandamus had been filed with the Florida Supreme Court. The secret was out that he was a fake prosecutor, so why would he still be acting like one? This prompted Dimanche to check the docket. That’s when he discovered that he had a warrant for his arrest.

It all made sense now. Edwards felt that if Dimanche had been languishing in jail, he wouldn’t have the resources to litigate the mandamus, and Edwards wouldn’t have to answer for usurping the authority of a prosecutor, as long as Dimanche was behind bars. That’s why he left the voicemail about no foreseeable courtdates. He called Dimanche again, but this time he had an offer: If Dimanche dismissed his mandamus petition in the 6th DCA and the appeal of Mendoza’s remand order in the Eleventh Circuit, judge Calderon would quash the capias and allow Dimanche to enter a guilty plea for the misdemeanors, and Dimanche wouldn’t have to serve any jail time.

Dimanche was extorted into dismissing his appeals because Carlos Mendoza didn’t want to get reversed by the Eleventh Circuit, Edwards didn’t want to get disbarred, and Calderon wanted to be the hero for Julia Frey.

Dimanche was forced to take the plea deal, Edwards dropped the felonies, and Calderon quashed the warrant. But there was a BIG problem:

The civil rights lawsuit.

Rigging the Case

Enter federal magistrate judge Daniel C. Irick.

The most misunderstood provision of the United States Constitution is Article III. All Americans who find themselves involved in litigation have a Constitutional right to what is known as an Article III judge, a judge who has been nominated by a president, confirmed by the Senate, and enjoys life tenure on the bench. But what a lot of people do not know is that there is a such thing as an Article I judge, judges whose authority was created by Congress at some point after the Constitution was created. In 1968, the Magistrates Act created the magistrate judge, a judge created by an Act of Congress, and not Article III of the Constitution.

This is where the magistrate arrives, at law. If a clerk of a district court announces a job opening for a magistrate position, any lawyer can put in an application to become a magistrate. It’s no different than a job you can find on Indeed.com. No presidential nomination, no Senate scrutiny for months, no media attention, and worst of all, no election. Daniel Irick filled out an application and got the job after he was hired by Middle District of Florida Chief Judge Timothy J. Corrigan.

In a federal lawsuit, magistrate judges are not permitted to act because they do not have Article III powers and jurisdiction. However, there are scenarios where magistrate judges can exercise power over cases: when all parties sign a written stipulation allowing a magistrate judge to exercise what is known as “civil-consent jurisdiction” (It’s also known as “experimentation” by district court judges). But ALL parties have to be in agreement. It is no different than signing away your life when undergoing a dangerous medical procedure, or selling all of your data over to Big Tech. But if just one person says “No”, the magistrate’s involvement is over.

At the outset of his Civil Rights lawsuit, Dimanche and counsel for the defendants filed a written stipulation that the parties did not consent to the civil-consent jurisdiction of a magistrate judge. This should have been the end of the issue, but Daniel Irick couldn’t let this case slip out of his hands. For one, Dimanche was a candidate in the City of Orlando’s general election for mayor, and two, Irick’s good friend, incumbent mayor Buddy Dyer, was a defendant in the case. Irick couldn’t allow for Dimanche to prevail.

After the extortion over the plea deal, Dimanche returned to the federal courthouse to reopen his Civil Rights lawsuit. Irick and Mendoza had imposed a stay on the case until the state court proceedings were over. They both expected Dimanche to abandon the lawsuit in light of the plea deal. However, Dimanche did the opposite: he resumed the lawsuit, and added additional defendants. Calderon, Blechman, Nunez-Navarro, Edwards, Wallsh, Stokes, the clerks who had fraudulently forfeited Dimanche’s bond, Julia Frey’s law firm, and many more defendants were added to the lawsuit. This certainly didn’t sit well with the magistrate judge, or Mendoza.

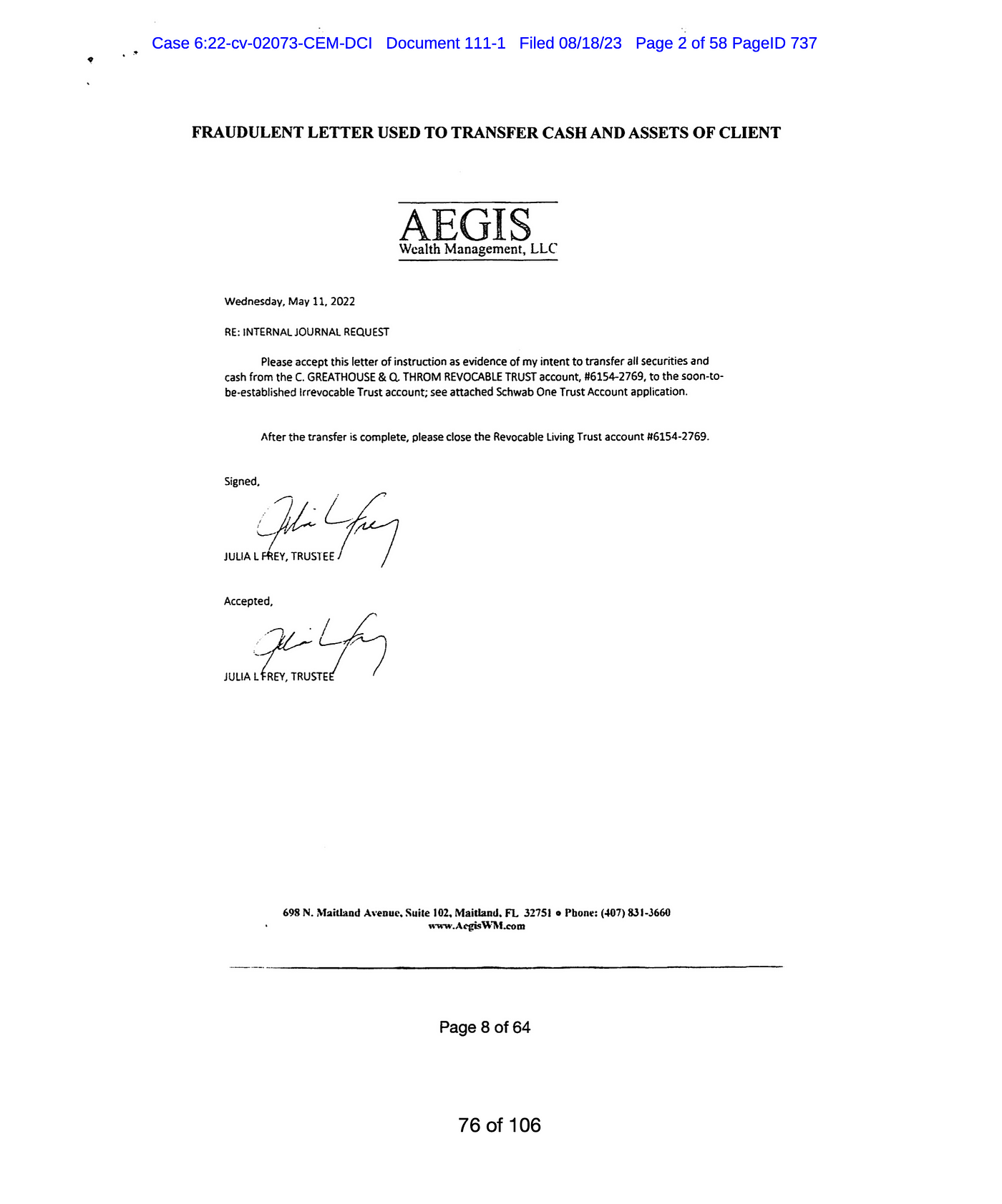

When the stay on the case was lifted, they were surprised to learn that Dimanche had procured bank records from Charles Schwab demonstrating how Julia Frey had committed wire fraud to open an account and transfer all of her deceased client’s money into a bank account she controlled. She sent a letter to Charles Schwab pretending to be a wealth management advisor from a company called “Aegis Wealth Management L.L.C.”, who was supposedly managing an IRA for the deceased woman (who had mysteriously died in Julia Frey’s company).

The first thing Irick did upon recommending that the case be reopened was dismiss the bank records as irrelevant.

This was a red flag.

Irick could have only been equally as corrupt as the state court judges. And the only way for him to be corrupt like that with impunity is for the district court judge, Carlos E. Mendoza, to be a corrupt judge as well. This caused Dimanche to begin investigating the magistrate and the district judge, and the findings were just as alarming as what Dimanche had learned about the state court judges.

Dimanche went back into the federal docket for the Removal case. It was there that he discovered what was perhaps the primary reason Mendoza had Calderon and Edwards extort Dimanche into dismissing the Eleventh Circuit appeal:

Mendoza had falsified the transcripts.

Falsified Transcripts

It was a frightening revelation, but the entire ordeal consisted of corruption of epic proportions. Mendoza and his court reporter, Suzanne Trimble, had falsified the parts of the transcripts that reflected the fact that Richard Wallsh was required to give testimony about his relationship with Julia Frey. The falsified version of the transcripts made the discussion at the evidentiary hearing seem like Wallsh’s testimony was never an issue. Mendoza even changed his own commands about requiring Wallsh to testify into him supposedly telling Stokes that Wallsh didn’t need to testify at all.

Digging deeper, Dimanche discovered an organization called the Fabulous Friends of Menello Museum and a video of Daniel Irick popping champaign bottles and raising a toast to Buddy Dyer at a fundraiser for a project that raised 20 million dollars.

Fraud, falsified documents, financial interests, conflicts of interest? The corruption seemed to have no end. So Dimanche employed a very rare legal mechanism in order to get the entire ordeal out of the local jurisdiction and back into the Eleventh Circuit:

An Emergency Petition for a Writ of Prohibition.

This was a way to ask the Eleventh Circuit to step into their supervisory role and do something about everything that was happening in Orlando.

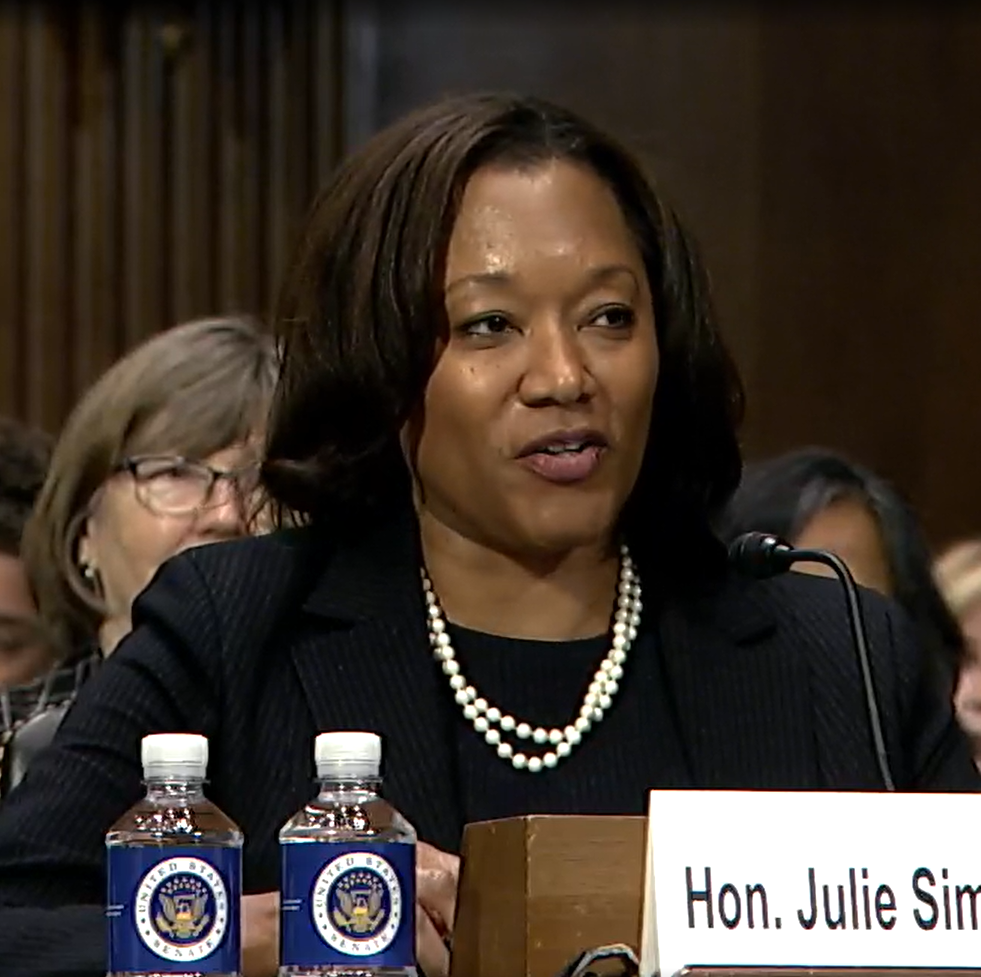

During the four-month wait for the Eleventh Circuit to take action, Dimanche published the falsified transcripts and his own corrected and truthful version into the Civil Rights case, demonstrating that Mendoza was a corrupt judge. After this evidence was entered into the record, Mendoza was kicked off of the case and the case was reassigned to district judge Julie S. Sneed, as soon as she had been appointed to the bench by president Joe Biden.

This was a very bad idea, given the complexity of the case, the sensitive issues involved, and the high stakes surrounding the naked corruption. The case should not have gone to a new judge.

After four months of considering the Emergency Petition for a Writ of Prohibition, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals denied the writ and opined that Dimanche could file motions in the district court asking the judges to disqualify themselves from the case instead of asking the Eleventh Circuit to exercise their supervisory jurisdiction.

This was the pathway to SCOTUS.

SCOTUS: Supervisory Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court of the United States typically exercises what is known asdiscretionary jurisdiction over cases. The issues before them are carefully considered for questions of great public importance, conflicting opinions amongst the Circuit courts, or death penalty cases. But there is a way that jurisdiction can be manifested at SCOTUS that is rarely pursued:

When SCOTUS has what is known as supervisory jurisdiction.

In order for the supervisory jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the United States to be invoke, a Circuit Court must have sanctioned very bad conduct in a district court. By the Eleventh Circuit refusing to issue the Writ of Prohibition, they sanctioned Mendoza falsifying those transcripts. They sanctioned Irick usurping jurisdiction in order to rig the case on behalf of the Fabulous Friends of Menello Museum. They sanctioned Andrew Edwards pretending to be a prosecutor. They sanctioned Calderon issuing that bogus warrant. They sanctioned Beamer issuing the coverup warrant. They sanctioned Montes kidnapping Dimanche. They sanctioned the home invasion. They sanctioned the weaponization of the government by a deep state law firm in order to assist Julia Frey’s unjust enrichment at the expense of the elderly citizens of Orlando.

Not even SCOTUS knows the full extent of its supervisory jurisdiction. The issue rarely makes its way there, and this topic has been the focus of past writings by Justice Amy Coney Barrett. She has stated in the past that the high court needs to explore that power more so that there is a better understanding of when SCOTUS must exercise that power, and what exactly it entails.

While rare at law, it seems there has always been a mechanism at law to resolve issues of judicial corruption when they seem insurmountable. Justice Elena Kagan recently stated that all of the laws of this country have an enforcement mechanism. In one week, September 30th, 2024, we will see how systemic corruption is resolved at SCOTUS, given the mechanism that is its supervisory jurisdiction.

What will they do? Nobody knows. Votes on certiorari are secret. They did offer everyone involved an opportunity to state their say in the matter, and nobody spoke up. Dimanche’s petition certainly raises issues of great public importance because the petition was initially styled by Dimanche as “Dimanche v. Lowndes, Drosdick, Doster, Kantor & Reed P.A.”, but SCOTUS restyled the case to “Moliere Dimanche v. United States District Court for the Middle District of Florida”, probably because they deemed the lower court responsible for the way things played out.

Daniel Irick’s actions exposed the vulnerabilities in the Federal Magistrates Act, and SCOTUS has been presented with the issue of whether or not the Act is unconstitutional. Andrew Edwards masquerading as a prosecutor will have a direct impact on the Federal prosecution of Donald Trump because it puts the issue of fake prosecutors squarely before the Court, which the litigation brought by Donald Trump did not do. SCOTUS also faces the question of ambiguity in its recent Thompson v. Clark decision, which should have been quite clear. However, if a fake prosecutor doesn’t have authority to prosecute, are the worthless convictions he secures a “favorable termination” within the meaning of the Thompson holding?

Orlando created a mess that can only be straightened out with new and impactful precedent being set in the highest Court in the land. The case exemplifies everything the People fear the most about corruption and a tyrannical government compromised by money and crime.

And what about the Magistrates Act? What will happen if SCOTUS strikes it down? If they do, surely the more than 12,000 magistrate judges currently serving will have to be replaced by 12,000 new district court judges. Which president will hold the nominating power for what could be the biggest shift to the judiciary in decades?

We will find out in Part 2 of what could be the most consequential October Surprise in American history.